‘No gloves, no masks’: Romania medical workers fear for lives

by Mihaela Rodina | Ionut Iordachescu

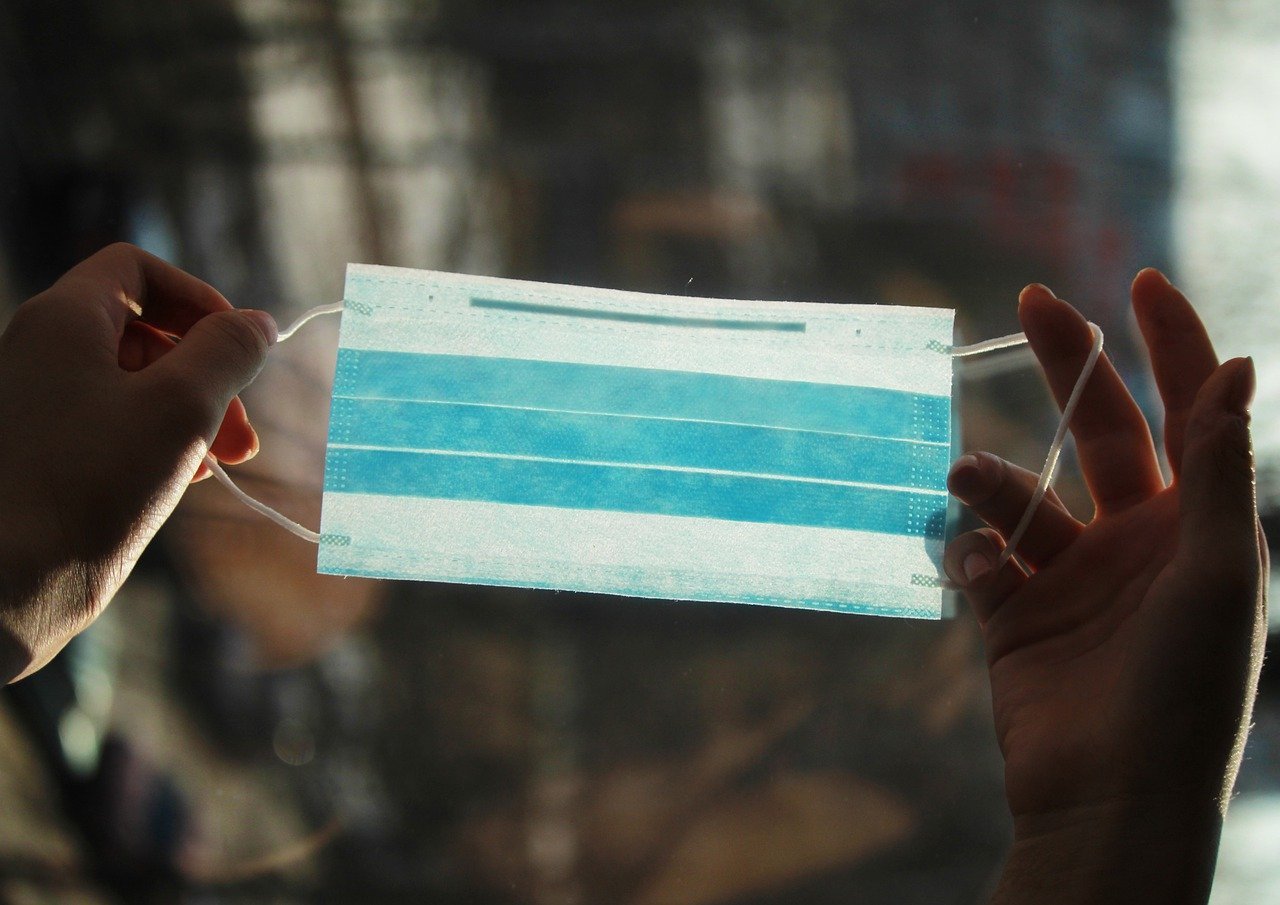

“We don’t have gloves, masks, anything,” says one of the medical team at southeastern Romania’s Ramnicu Sarat hospital, one of those designated to treat COVID-19 patients.

“Everything is done on the cheap,” protests the staff member, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

It’s a complaint echoed in other parts of the country, where doctors and nurses have begun speaking out about what they say are life-threatening shortcomings in the fight against the new coronavirus.

Feeling ill-equipped and scared, some have taken to social media or public TV to voice their concerns; dozens staged protests in the grounds of two hospitals.

Several felt so strongly that they resigned, leaving an already struggling healthcare system in one of the European Union’s poorest countries even more vulnerable.

“Nobody instructed us so we’re encouraged to learn from videos,” the Ramnicu Sarat medical staff member told AFP.

“We were promised equipment, but when will it arrive?”

The hospital has been placed on a long list of “support units” selected to receive patients who have tested positive for COVID-19.

But the move has sparked fear among local residents that the virus could spread in the area and an online petition has been launched.

‘Lack of trust’

Since 2007 when Romania joined the EU, more than 14,000 healthcare workers have emigrated in search of better pay and conditions abroad.

On Monday alone, 10 nurses and one intensive care unit (ICU) medic from central Hunedoara county quit, blaming a chronic lack of basic medical equipment such as surgical masks and gloves.

A day later, the nurses — but not the doctor — were persuaded by officials to change their minds and go back to work.

“We have two medical gowns for 12 employees…,” the doctor, Lorena Ehim, told local media, adding they were being forced to face the virus and risk their health “with bare hands”.

At a hospital in the western city of Timisoara, 13 medical staffers resigned on Tuesday, according to local media.

“I can understand my colleagues who step down, but I don’t encourage resignation,” Gheorghe Borcean, president of Romania’s medical association, told AFP.

“Even more than fear (of infection), there is a lack of trust in the medical system,” he said.

Romania, as of Wednesday, had confirmed more than 2,450 cases of COVID-19 — about 300 of them medical workers — and 86 deaths.

The government has promised to get more protective gear for medical staff.

It also considered banning resignations but decided against, fearing such a move would fuel more resentment.

“We’re looking at you with hope. The coming days will be even tougher, but we’ll do our best to give you protective gear,” President Klaus Iohannis told medical staff on Tuesday in a press statement.

Hospital as hotspot

Doctors are also critical of the state of ICU units, which risk being overwhelmed soon in a country of 19 million people, with the outbreak expected to peak in the middle of this month.

On paper, Romania has 5,111 ICU beds, but fewer than half of those are equipped with a ventilator, according to Health Minister Nelu Tataru.

For the past three decades, the system has been plagued by widespread corruption and a lack of investment.

Romania spends just over five percent of its gross domestic product on health care, the lowest ratio in the EU, according to Eurostat data.

Sfantul Ioan Emergency Hospital in the northeastern city of Suceava has become the centre of the country’s coronavirus outbreak.

The hospital was forced to close after dozens of staff members became infected.

Prosecutors have opened an investigation on suspicions that “measures taken to prevent and limit the spread of the novel coronavirus weren’t respected”.

But Sfantul Ioan hospital doctor Mircea Dinu Bordiniuc said on RFI Romania radio that not all medical personnel were tested.

“It’s an error of public health to ask medical personnel, who should have been in isolation, to go to work,” he said.

Suceava and its surrounding region, close to the Ukrainian border, has seen around 400 coronavirus cases, half of which involve doctors and nurses.

Some 30 people infected with the virus have died.

The city of 100,000 inhabitants includes many emigrants who recently returned from Italy or France, contributing to the virus’ spread, and was placed in quarantine earlier this week. (AFP)